- Home

- Burt L. Standish

Wild Adventures round the Pole

Wild Adventures round the Pole Read online

Produced by Nick Hodson of London, England

Wild Adventures round the PoleThe Cruise of the "Snowbird" Crew in the "Arrandoon"By Gordon StablesPublished by Hodder and Stoughton, 27 Paternoster Row, London.This edition dated 1883.

Wild Adventures round the Pole, by Gordon Stables.

________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________WILD ADVENTURES ROUND THE POLE, BY GORDON STABLES.

CHAPTER ONE.

THE TWIN RIVERS--A BUSY SCENE--OLD FRIENDS WITH NEW FACES--THE BUILDINGOF THE GREAT SHIP--PEOPLE'S OPINIONS--RALPH'S HIGHLAND HOME.

Wilder scenery there is in abundance in Scotland, but hardly will youfind any more picturesquely beautiful than that in which the two greatrivers, the Clyde and the Tweed, first begin their journey seawards. Itis a classic land, there is poetry in every breath you breathe, the veryair seems redolent of romance. Here Coleridge, Scott, and Burns roved.Wilson loved it well, and on yonder hills Hogg, the Bard of Ettrick--hewho "taught the wandering winds to sing"--fed his flocks. It is a land,too, not only of poetic memories, but one dear to all who can appreciatedaring deeds done in a good cause, and who love the name of hero.

If the reader saw the rivers we have just named, as they roll theirwaters majestically into the ocean, the one at Greenock, the other nearthe quaint old town of Berwick, he would hardly believe that at thecommencement of their course they are so small and narrow thatordinary-sized men can step across them, that bare-legged little boyswade through them, and thrust their arms under their green banks,bringing therefrom many a lusty trout. But so it is.

Both rise in the same district, within not very many miles of eachother, and for a considerable distance they follow the same directionand flow north.

But soon the Tweed gets very faint-hearted indeed.

"The country is getting wilder and wilder," she says to her companion,"we'll never be able to do it. I'm going south and east. It iseasier."

"And I," says the bold Clyde, "am going northwards and west; it is moredifficult, and therein lies the enjoyment. I will conquer everyobstacle, I'll defy everything that comes against me, and thus I'll be amightier river than you. I'll water great cities, and on my broadbreast I will bear proud navies to the ocean, to do battle against windand wave. `Faint heart never won fair lady.' Farewell, friend Tweed,farewell."

And so they part.

This conversation between the two rivers is held fourteen hundred feetabove the level of the sea, and five score miles and over have to betraversed before the Clyde can reach it. Yet, nothing daunted, merrilyon she rolls, gaining many an accession of strength on the way fromstreams and burns.

"If you are going seaward," say these burns, "so are we, so we'll takethe liberty of joining you."

"And right welcome you are," sings the Clyde; "in union lies strength."

In union lies strength; yes, and in union is happiness too, it wouldseem, for the Clyde, broader and stronger now, glides peacefully andsilently onwards; or if not quite silently, it emits but a silverymurmur of content. Past green banks and wooded braes, through daisiedfields where cattle feed, through lonely moorlands heather-clad, nowhidden in forest depths, now out again into the broad light of day,sweeping past villages, cottages, mansions, and castles, homes of serfand feudal lord in times long past and gone, with many a sweep and manya curve it reaches the wildest part of its course. Here it must rush,the rapids and go tumbling and roaring over the lynns, with a noise thatmay be heard for miles on a still night, with an impetuosity that shakesthe earth for hundreds of yards on every side.

"I wonder how old Tweed is getting on?" thinks our brave river as soonas it has cleared the rocks and rapids and pauses for breath.

But the Clyde will soon be rewarded for its pluck and its daring, beforelong it will enter and sweep through the second city of the empire, thegreat metropolis of the west; but ere it does so, forgive it, if itlingers awhile at Bothwell, and if it seems sullen and sad as it dashesunderneath the ancient bridge where, in days long gone, so fierce afight took place that five hundred of the brave Covenanters lay dead onthe field of battle. And pardon it when anon it makes a grand andsplendid sweep round Bothwell Bank, as if loth to leave it. Yonder arethe ruins of the ancient castle--

"Where once proud Murray held the festive board. ***** But where are now the festive board, The martial throng, and midnight song? Ah! ivy binds the mouldering walls, And ruin reigns in Bothwell's halls. O, deep and long have slumbered now The cares that knit the soldier's brow, The lovely grace, the manly power, In gilded hall and lady's bower; The tears that fell from beauty's eye, The broken heart, the bitter sigh, E'en deadly feuds have passed away, Still thou art lovely in decay."

But see, our river has left both beauty and romance far behind it. Ithas entered the city--the city of merchant princes, the city of athousand palaces; it bears itself more steadily now, for hath not QueenCommerce deigned to welcome it, and entrusted to it the floating wealthof half a nation? The river is in no hurry to leave this fair city.

"My noble queen," it seems to say, "I am at your service. I come fromthe far-off hills to obey your high behests. My ambition is fulfilled,do with me as you will."

But soon as the bustle and din of the city are led behind, soon as thegrand old hills begin to appear on the right, and glimpses of green onthe southern banks, lo! the tide comes up to welcome the noble river;and so the Clyde falls silently and imperceptibly into the mightyAtlantic. Yet scarcely is the lurid and smoky atmosphere that hangspall-like over the town exchanged for the purer, clearer air beyond,hardly have the waters from the distant mountains begun to mingle withocean's brine, ere the noise of ten thousand hammers seems to rend thevery sky.

Clang, clang, clang, clang--surely the ancient god Vulcan hasreappeared, and taken up his abode by the banks of the river. Clang,clang, clang. See yonder is the _Iona_, churning the water into foamwith her swift-revolving paddles. She has over a thousand passengers onboard; they are bound for the Highlands, bent on pleasure. But thisterrible noise and din of hammers--they will have three long miles of itbefore they can even converse in comfort. Clang, clang, clang--it is nomusic to them. Nay, but to many it is.

It is music to the merchant prince, for yonder lordly ship, when she islaunched from the slips, will sail far over the sea, and bring him backwealth from many a foreign shore. It is music to the naval officer; ittells him his ship is preparing, that ere long she will be ready forsea, that his white flag will be unfurled to the breeze, and that hewill walk her decks--her proud commander.

And it is music--merry music to the ears of two individuals at least,who are destined to play a very prominent part in this story. They arestanding on the quarter-deck of a half-completed ship, while clang,clang, clang, go the hammers outside and inside.

The younger of the two--he can be but little over twenty-three--withfolded arms, is leaning carelessly against the bulwarks. Although thereis a thoughtful look upon his handsome face, there is a smile as well, asmile of pleasure. He is taller by many inches than his companion,though by no means better "built," as sailors call it. This companionhas a bold, brown, weather-beaten face, the lower half of it buried in abeard that is slightly tinged with grey; his eyes are clear andhonest,--eyes that you can tell at a glance would not flinch to meeteven death itself. He stands bold, erect, firm. Both are dressed well,but there is a marked difference in the style of their attire. Thegarments of the elder pronounce him at once just what he is,--one whohas been "down to the sea in ships." The younger is dressed in thefashionable attire of an English gentleman. To say more were needless.A min

ute observer, however, might have noticed that there was a slightair of _neglige_ about him, if only in the unbuttoned coat or thefaultless hat pushed back off the brow.

"And so you tell me," said the younger, "that the work still goesbravely on?"

"Ay, that it does," said his companion; "there have been rumours of astrike for higher wages among the men of other yards, but none, I amproud to say, in this."

"And still," continued the former, "we pay but a fraction of wage morethan other people, and then, of course, there is the extra weeklyhalf-holiday."

"There is something more, Ralph--forgive me if I call you Ralph, inmemory of dear old times. You will always be a boy to me, and I couldno more call you Mr Leigh than I could fly."

Ralph grasped his companion by the hand; the action was but

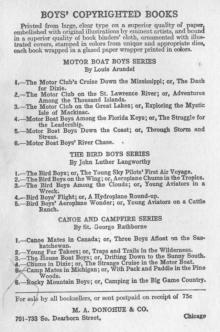

Dick Merriwell Abroad; Or, The Ban of the Terrible Ten

Dick Merriwell Abroad; Or, The Ban of the Terrible Ten Wild Adventures round the Pole

Wild Adventures round the Pole Storm-Bound; or, A Vacation Among the Snow Drifts

Storm-Bound; or, A Vacation Among the Snow Drifts In the Yellow Sea

In the Yellow Sea Frank Merriwell's Triumph; Or, The Disappearance of Felicia

Frank Merriwell's Triumph; Or, The Disappearance of Felicia Treasure of Kings

Treasure of Kings Bert Wilson's Twin Cylinder Racer

Bert Wilson's Twin Cylinder Racer Frank Merriwell's Backers; Or, The Pride of His Friends

Frank Merriwell's Backers; Or, The Pride of His Friends Endurance Test; or, How Clear Grit Won the Day

Endurance Test; or, How Clear Grit Won the Day Great Hike; or, The Pride of the Khaki Troop

Great Hike; or, The Pride of the Khaki Troop The Swan and Her Crew

The Swan and Her Crew A cup of sweets, that can never cloy: or, delightful tales for good children

A cup of sweets, that can never cloy: or, delightful tales for good children Frank Merriwell's Bravery

Frank Merriwell's Bravery Frank Merriwell Down South

Frank Merriwell Down South Dick Merriwell's Trap; Or, The Chap Who Bungled

Dick Merriwell's Trap; Or, The Chap Who Bungled The Trail of the Seneca

The Trail of the Seneca Wild Life in the Land of the Giants: A Tale of Two Brothers

Wild Life in the Land of the Giants: A Tale of Two Brothers From Squire to Squatter: A Tale of the Old Land and the New

From Squire to Squatter: A Tale of the Old Land and the New The Cruise of the Snowbird: A Story of Arctic Adventure

The Cruise of the Snowbird: A Story of Arctic Adventure Owen Clancy's Happy Trail; Or, The Motor Wizard in California

Owen Clancy's Happy Trail; Or, The Motor Wizard in California Boy Scouts: Tenderfoot Squad; or, Camping at Raccoon Lodge

Boy Scouts: Tenderfoot Squad; or, Camping at Raccoon Lodge Sing a Song of Sixpence

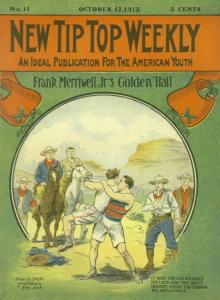

Sing a Song of Sixpence Frank Merriwell's New Comedian; Or, The Rise of a Star

Frank Merriwell's New Comedian; Or, The Rise of a Star The Sa'-Zada Tales

The Sa'-Zada Tales The Girl Scout's Triumph; or, Rosanna's Sacrifice

The Girl Scout's Triumph; or, Rosanna's Sacrifice Wild Adventures in Wild Places

Wild Adventures in Wild Places Fairies I Have Met

Fairies I Have Met Frank Merriwell's Son; Or, A Chip Off the Old Block

Frank Merriwell's Son; Or, A Chip Off the Old Block Motor Boat Boys' River Chase; or, Six Chums Afloat and Ashore

Motor Boat Boys' River Chase; or, Six Chums Afloat and Ashore Frank Merriwell's Athletes; Or, The Boys Who Won

Frank Merriwell's Athletes; Or, The Boys Who Won Bart Keene's Hunting Days; or, The Darewell Chums in a Winter Camp

Bart Keene's Hunting Days; or, The Darewell Chums in a Winter Camp Captain June

Captain June