- Home

- Burt L. Standish

A cup of sweets, that can never cloy: or, delightful tales for good children Page 2

A cup of sweets, that can never cloy: or, delightful tales for good children Read online

Page 2

"Good night, my dear Fanny! Pray give my duty to dear mamma, and believe me,

"Your most affectionate sister,

"CECILIA."

Fanny was delighted at receiving this letter, and wrote the followinganswer to her sister:

"MY DEAR CECILIA,

"How glad I am to hear that you are so happy in the country! I should certainly like very much to be with you, but not to leave mamma alone; and she is so good, that I am not half so lonely as I thought I should be in your absence. Only think, my dear sister! she has bought me the sweetest little goldfinch you ever saw, and it is so tame, that the moment I come near the cage, it jumps down from its perch to see what I have got for it.

"But this is not all: she has taken me to a shop, and bought me a great many pretty prints, which I am sure you will have great pleasure in looking at when you come home. We have been twice at M---- to spend the day; and indeed, my dear Cecilia, I have had a great deal of pleasure, though perhaps not quite so much as you have had in your fields and meadows, and among your haymakers; but mamma says we may be happy in any place if we choose it, and will determine to make ourselves contented, instead of spending our time in wishing ourselves in other places than where we are: and I am sure she is very right, for if I were to fret and vex myself because I am not in the country, and you do the same because you are not in town, my goldfinch and my prints, my pleasant walks in the gardens at M----, and all mamma's kindness, would be lost upon me, and you would have no pleasure in your little garden, or in looking at the haymakers, your shells, your sea-weeds, or any of the curiosities you meet with.

"Pray, dear Cecilia, let me have one more letter from you before you come home, and do not burn mine, for I shall like to see how much better I write next year; and so will you, I dare say, so I shall lock up your letters in my little work-trunk.

"Mamma desires her best love to you. Give my duty to my aunt, and believe me

"Your affectionate sister,

"FANNY."

It was almost a fortnight before Fanny heard again from her sister, whenone morning a basket, covered very closely, and a small parcel, with aletter tied upon it, were brought up stairs, and placed upon the tablebefore her. The letter was from her sister, and contained the followingwords:

"MY DEAR FANNY,

"You would have heard from me much sooner, but I waited to write by George, whom my aunt told me she should be obliged to send to town on business. He brings you a basket of strawberries from her, with her love to you: fourteen of them are from _our_ garden, and I assure you I had a pleasure in picking them, which I cannot describe: they are in a leaf by themselves, and I beg you will let me know if they are ripe and sweet, for I did not taste them; I was determined to send you all the first. I send you also a little parcel of shells and sea-weeds, and when I am with you, I will teach you how to make very pretty pictures of them, as my aunt has had the goodness to teach me.

"I have been very happy here, though I could not persuade myself to believe it possible when I first came, because I could not have mamma and you with me; but I shall remember her advice, and always endeavour to be pleased, and find amusement where I am, and with what I have, instead of fretting, like our cousin Emily, because she had not a blue work-bag instead of a pink one, or because see had an ivory toothpick-case given to her when she was wishing for a tortoise-shell one.

"My aunt says, that children who do so are so very tiresome, that they make themselves disliked by every body, and that they are never invited a second time to a house, because people are generally tired of their company on the first visit.

"I hope I shall see you and my dearest mamma next week; but you may write to me by George, for I shall be very much disappointed if he returns without a letter from you.--Adieu! dear Fanny.

"I am affectionately yours,

"CECILIA."

Fanny had only time to write a short note to her sister, which Georgecalled for soon after dinner; and Cecilia's return the following week,put an end to the correspondence for that time. The two sisters wereextremely happy to meet, though they had not made themselvesdisagreeable, and teased people with their ill humour when they wereseparated; and they were very well convinced, that if they had done so,they should have suffered by it, and have been very uncomfortable.

The following summer Fanny paid a visit to her aunt, and had thepleasure of finding their little garden in such good order, and so manystrawberries in it, that she could send her sister a basket-full. Shecould work very neatly; and her aunt having given her a large parcel ofsilks, riband, twist, and gold cord, she made the prettiest pincushionsthat ever were seen, to send to her mamma, her sister, and her cousins.

Cecilia was extremely fond of drawing, and was so attentive to herlessons during her sister's absence, that she had a portfolio full ofpretty things to shew her on her return.

No little girls in the world could be happier than Cecilia and Fanny,and the reason of it is very plain: they were always obedient to theirmamma's commands, kind to the servants, and obliging to every body;always contented with what they had, and in whatever place they happenedto be; and never fretful and out of humour for want of something to do,for they had endeavoured to learn every thing when they had anopportunity of doing so, that they might never be at a loss foremployment and amusement.

HENRY.

Henry was the son of a merchant of Bristol: he was a very good-natured,obliging boy, and loved his papa and mamma, and his brothers andsisters, most affectionately; but he had one very disagreeable fault,which was, that he did not like to be directed or advised, but alwaysappeared displeased when any body only hinted to him what he might, orwhat he ought not to do; he fancied he knew right from wrong perfectlywell, and that he did not require any one to direct him.

He was the most amiable boy in the world, if you would let him have hisown way: he never heard any body say they wished for a thing, that hedid not run to get it for them, if it was in his power; and no one couldbe more ready to lend his toys to his brothers and sisters, wheneverthey appeared to desire them: but the moment he was told not to stand sonear the fire, or not to jump down two or three stairs at a time, not toclimb upon the tables, or to take care he did not fall out of thewindow, he grew directly angry, and asked if they thought he did notknow what he was about--said he was no longer a baby, and that he wascertainly big enough to take care of himself.

His friends were extremely sorry to perceive this fault in hisdisposition, for every body loved him, and wished to convince him,that, though he was not a baby, he was but a child; and that if he wouldavoid getting into mischief, he must, for some years, submit to bedirected by his papa and mamma, and, in their absence by some otherperson who knew better than he did: but he never minded their advice,till he had one day nearly lost his life by not attending to it.

A lady, who visited his mamma, and who was extremely fond of him, methim in the hall on new year's day, and gave him a seven shilling pieceto purchase something to amuse himself.--Henry was delighted at havingso much money; but instead of informing his parents of the present hehad received, and asking them to advise him how to spend it, hedetermined to do as he liked with it, without consulting any body; andhaving long had a great desire to amuse himself with some gunpowder, hebegan to think (now he was so rich) whether it might not be possible tocontrive to get some. He had been often told of the dreadful accidentswhich have happened by playing with this dangerous thing, but he fancied_he_ could take care, _he_ was old enough to amuse himself with it,without any risk of hurting himself; and meeting with a boy who wasemployed about the house by the servants, he offered to give him ashilling for his trouble, if he would get him what he desired; and asthe boy cared very little for the danger to which he exposed Henr

y, ofblowing himself up, so as he got but the shilling, he was soon inpossession of what he wished for.

A dreadful noise was, some time afterwards, heard in the nursery. Thecries of children, and the screams of their maid, brought the wholefamily up stairs: but oh! what a shocking sight was presented to theirview on opening the door! There lay Henry by the fireside, his faceblack, and smeared with blood; his hair burnt, and his eyes closed: oneof his little sisters lay by him, nearly in the same deplorablecondition; the others, some hurt, but all frightened almost to death,were got together in a corner, and the maid was fallen on the floor in afit.

It was very long before either Henry or his sister could speak, and manymonths before they were quite restored to health, and even then withthe loss of one of poor Henry's eyes. He had been many weeks confined tohis bed in a dark room, and it was during that time that he hadreflected upon his past conduct: he now saw that he had been a veryconceited, wrong-headed boy, and that children would avoid a great manyaccidents which happen to themselves, and the mischiefs they frequentlylead others into, if they would listen to the advice of their elders,and not fancy they are capable of conducting themselves without beingdirected; and he was so sorry for what he had done, and particularly forwhat he had made his dear little Emma suffer, that he never afterwardsdid the least thing without consulting his friends; and whenever he wastold not to do a thing, though he had wished it ever so much, insteadof being angry, as he used to be, he immediately gave up all desire ofdoing it, and never after that time got into any mischief.

MARIA;

OR,

THE LITTLE SLATTERN.

Little Maria B---- was so slatternly, and so careless of her clothes,that she never was fit to appear before any body, without being firstsent to her maid to be new dressed. If she came to breakfast quite niceand clean, before twelve o'clock you could scarcely perceive that herfrock had ever been white: her face and hands were always dirty, herhair in disorder, and her shoes trodden down at the heels, because shewas continually kicking them off.

At dinner no one liked to sit near her, for she was sure to throw hermeat into their laps, pull about their bread with her greasy fingers,and never failed to overset her drink upon the table-cloth.

One day her brother ran into the nursery in great haste, desiring shewould go down with him immediately into the parlour, and telling her,that a gentleman had brought a large portfolio, full of beautiful printsof all kinds of birds and animals, which he was going to shew to them,if they were ready to come to him directly, for he could not stay withthem, he said, more than half an hour.

Poor Maria was in no condition to shew herself; she had been washingher doll's clothes (though her maid had desired her not to do it, andhad promised to wash them for her, if she would have patience till theafternoon), and had thrown a large basin of water all over her; afterwhich, wet as she was, she had been rummaging in a dirty closet, whereshe had no kind of business, and was, when her brother came into thenursery, covered with dust and cobwebs.

Susan was called in haste to new-dress her; but she was so extremelycareless of her clothes, and tore them so much every day, that oneperson was scarcely sufficient to keep them in order for her. Not afrock was to be found, which had not the tucks ripped, and the stringsbroken, nor a pair of shoes fit to put on; her face and hands could notbe got clean without warm water, and that must be fetched from thekitchen; then she had to look for a comb, Maria had poked hers into amouse-hole, and had been rubbing the grate with her brush: in short, bythe time all was ready, and she was dressed, a full hour had slippedaway without her perceiving it.

Down stairs, however, she went, opened the parlour-door, and was justgoing to make a fine courtesy to the gentleman and his portfolio, whento her very great surprise and mortification, she perceived her mammasitting alone, at work by the fire. The gentleman had shewn his printsto her brothers and sisters, made each of them a present of a verypretty one, and had been gone some time.

When her aunt came from Bath, she brought her a nice green silk bonnet,and a cambric tippet, tied with green riband. Maria was very muchdelighted with it, and fancied she looked so well in it, that she couldnot be prevailed upon to pull it off; but she soon forgot that it wasnew and very pretty, and ought to be taken care of; she thought ofnothing, when she could escape from her maid, but of getting into holesand corners; and having rambled into an old back kitchen, and findingherself too warm, she took off her pretty green bonnet, and threw itdown on the ground, but recollecting something she had now anopportunity of doing, ran away in great haste, and left it there.

When she was asked what she had done with her bonnet, she said she didnot know, and the servants lost their time in seeking for it; for whowould have thought of looking for a young lady's bonnet in a dirty backkitchen?

There, however, it was found, with a black cat and four kittens lyingasleep in it, and so entirely spoiled, that it could never be worn anymore; and she was obliged to wear her old bonnet a great many monthslonger, for her mamma was extremely angry with her, and would not buyher a new one; nor did she deserve to have one, till she could learn totake more care of it, and not leave it about in such dirty places.

It is not very usual to see young ladies wandering about by themselvesin stables and outhouses, but Maria had very great pleasure in it, andnever lost the opportunity when she could get away without being seen;and she was so dirty, and had so often her clothes torn, that she wasfrequently taken by strangers for some poor child sent on an errand tothe servants.

One day, when she was passing through the gate to see who was comingdown the lane, a little boy upon an ass, who came up from the sea-sideevery week with fish, seeing her there doing nothing, called out, "Here,hark! you little girl, open the gate, I say--come, make haste, do notstand there like a post. What! are you asleep?"

Maria was so much ashamed, that she could not move, but hung down herhead, and the boy (who had a mind to make her save him the trouble ofgetting off from his ass) continued to talk to her in the polite mannerin which he had begun: "Why, you little dirty thing! open the gate Isay--if you do not, I will tell the cook of you, and she will tellMadam, and I shall get you turned out of the house."

Thus was Maria B---- continually mortified by one person or another, andlosing every pleasure and amusement which her brothers and sisters wereindulged in, because she was never ready to join in them. They oftenwent to walk in the charming woods and meadows which surrounded thehouse, and were sometimes sent with their maid to carry comfortablethings to their poor sick neighbours, from whom they received in returna thousand thanks and prayers to God for their happiness; but Mariacould have no share in either, for she was never with them, and theyknew nothing of her.

Once, when their grandpapa sent his coach to fetch them to dine withhim, Maria was not to be found; and, after seeking her all over thehouse to no purpose, they at length caught her in the garden with awatering pot, which she could hardly lift from the ground, her shoes wetand covered with mould, her frock in the same condition, and her handsand arms dirty quite up to the elbows. Her mamma positively declaredthat the horses should not be kept a moment longer, the coachman wasdesired to drive on, and Maria was left to spend the day in the nurseryfrom whence she was ordered not to stir.

There she spent a melancholy day indeed, for she had no means ofamusing herself to make time pass lightly on: she had no pleasure inreading, so that all the pretty books which had been bought for her wereof no use; she could not play with her doll, for it had no clothes, theywere all lost or burnt; and she had suffered a little puppy to play withher work-bag, till both that and the work which was in it, thread-case,cotton, and every thing else were all torn to pieces. The only thing shefound to do, was to sit down by the window, look at the road and cry,till her brothers and sisters returned, and then she had themortification of hearing them recount the pleasure they had enjoyed,talk of the curiosities their grandpapa had shewn them in the greatcloset at the end of the gallery, and of seeing all the pre

tty thingsthey had brought home with them, and of which she might have had hershare if she had been of their party.

FREDERICK'S HOLIDAYS.

"I wish," said Frederick to Mr. Peterson, "I could be with my aunt intown to spend the holidays; I shall be so tired here in the country, Ishall not know what to do with myself. Two of my schoolfellows live inthe next street to my aunt, and they will be going with their papa tothe play, and to Astley's, and to walk in the Park, and will have somuch more pleasure than I shall have--why, I might as well be atschool, as here sauntering about the fields."

"You are not very civil," answered Mr. Peterson. "When you came fromBarbadoes last year, and had no other acquaintance, you liked very wellto be with me in the holidays: however, if you desire it, my dearFrederick, you shall go to your aunt's, that you may be near your littlefriends, and I will write to their papa, to request that he will giveyou leave to be with them as much as possible, that you may partake ofall their pleasures, for I do not think you will have a great deal inyour aunt's house; you know she is always ill, and cannot have it in herpower to procure you much amusement."

Frederick was accordingly sent to town, and his first wish was to pay avisit to his two friends in the next street. His aunt's servant wasordered to conduct him to the house, and he was shewn immediately upstairs; but, instead of meeting with those he expected, he found theirpapa alone in the drawing-room, sitting at a table covered with papers,and apparently very busy.

On inquiring for his schoolfellows, he was very much surprised at beinginformed that they were gone into the country: "for," said their papa,"they would not have liked to be confined at home all their holidays,and I should have had no time to run about with them; they might as wellhave remained at school as have been here; but where they are gone theywill enjoy themselves; they will spend a week at their grandfather's,and from thence go to my good friend, Mr. Peterson's, where they willhave all the pleasure and amusement they can possibly wish for."

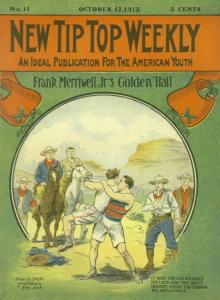

Dick Merriwell Abroad; Or, The Ban of the Terrible Ten

Dick Merriwell Abroad; Or, The Ban of the Terrible Ten Wild Adventures round the Pole

Wild Adventures round the Pole Storm-Bound; or, A Vacation Among the Snow Drifts

Storm-Bound; or, A Vacation Among the Snow Drifts In the Yellow Sea

In the Yellow Sea Frank Merriwell's Triumph; Or, The Disappearance of Felicia

Frank Merriwell's Triumph; Or, The Disappearance of Felicia Treasure of Kings

Treasure of Kings Bert Wilson's Twin Cylinder Racer

Bert Wilson's Twin Cylinder Racer Frank Merriwell's Backers; Or, The Pride of His Friends

Frank Merriwell's Backers; Or, The Pride of His Friends Endurance Test; or, How Clear Grit Won the Day

Endurance Test; or, How Clear Grit Won the Day Great Hike; or, The Pride of the Khaki Troop

Great Hike; or, The Pride of the Khaki Troop The Swan and Her Crew

The Swan and Her Crew A cup of sweets, that can never cloy: or, delightful tales for good children

A cup of sweets, that can never cloy: or, delightful tales for good children Frank Merriwell's Bravery

Frank Merriwell's Bravery Frank Merriwell Down South

Frank Merriwell Down South Dick Merriwell's Trap; Or, The Chap Who Bungled

Dick Merriwell's Trap; Or, The Chap Who Bungled The Trail of the Seneca

The Trail of the Seneca Wild Life in the Land of the Giants: A Tale of Two Brothers

Wild Life in the Land of the Giants: A Tale of Two Brothers From Squire to Squatter: A Tale of the Old Land and the New

From Squire to Squatter: A Tale of the Old Land and the New The Cruise of the Snowbird: A Story of Arctic Adventure

The Cruise of the Snowbird: A Story of Arctic Adventure Owen Clancy's Happy Trail; Or, The Motor Wizard in California

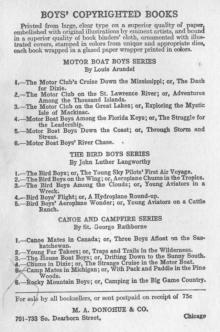

Owen Clancy's Happy Trail; Or, The Motor Wizard in California Boy Scouts: Tenderfoot Squad; or, Camping at Raccoon Lodge

Boy Scouts: Tenderfoot Squad; or, Camping at Raccoon Lodge Sing a Song of Sixpence

Sing a Song of Sixpence Frank Merriwell's New Comedian; Or, The Rise of a Star

Frank Merriwell's New Comedian; Or, The Rise of a Star The Sa'-Zada Tales

The Sa'-Zada Tales The Girl Scout's Triumph; or, Rosanna's Sacrifice

The Girl Scout's Triumph; or, Rosanna's Sacrifice Wild Adventures in Wild Places

Wild Adventures in Wild Places Fairies I Have Met

Fairies I Have Met Frank Merriwell's Son; Or, A Chip Off the Old Block

Frank Merriwell's Son; Or, A Chip Off the Old Block Motor Boat Boys' River Chase; or, Six Chums Afloat and Ashore

Motor Boat Boys' River Chase; or, Six Chums Afloat and Ashore Frank Merriwell's Athletes; Or, The Boys Who Won

Frank Merriwell's Athletes; Or, The Boys Who Won Bart Keene's Hunting Days; or, The Darewell Chums in a Winter Camp

Bart Keene's Hunting Days; or, The Darewell Chums in a Winter Camp Captain June

Captain June