- Home

- Burt L. Standish

Wild Adventures in Wild Places Page 2

Wild Adventures in Wild Places Read online

Page 2

kept aloof for a time until they drew a cover ortwo, until the mellow music of the hounds, mingling with the cheeringnotes of the huntsman's horn, told me they had found, and that the runhad commenced. Across country, straight almost as the crow could fly,for ten miles, that old fox led us. Then he changed course near aplantation, and took us five miles in another direction. Then, doublinground, he took us almost straight away back, so that the stragglers oncemore had a chance of joining the hunt. But the terribly rough state ofthe country told on all but the best of us, and if we were few in numberto start, we were still less numerous when the fox finally took to earthand refused to show again. A fine old gentlemanly fox, I can assureyou, who had apparently enjoyed the run as much as any of us, and havingdone so, bade us good-morning and retired.

"I had made acquaintance with the general, and we were laughing andtalking together when he suddenly started and turned pale.

"`Great heavens!' he cried, `it is Eenie, my daughter. Black Bess, hermare, has bolted with her, and is heading straight for the Furies' Leap.She is lost! she is lost!'

"I hardly heard the last word. I had struck the spurs into my own goodmare, and was off like a meteor. I could see the lady's terribledanger. She was heading for an awful precipice. I saw I mightintercept her if I crossed her bows, as a sailor would say. It was aride for life--we near each other, riding swift as arrows. Onward shecomes--onwards I dash, and we are barely fifty yards from the Furies'Leap, when our horses come into collision with fearful force.

"I remember nothing more until I open my eyes and find myself in bed,powerless to move. But a beautiful young girl rose from a seat near thewindow, and, approaching the bed, gave me to drink, but enjoined me tobe still. This was Miss Lyell; she nursed me back to life, and the nextfew weeks seemed all one happy dream."

"She loves you?"

"She does, and has promised never to be another's."

"And she'll be yours, Frank, my boy. Come, I've news to give you.Neither your father nor her father object, except on the score of youryouth and hers, and your inexperience of the world. Now, depend uponit, Frank, what your father advises is best. He wants you to spend yournext few years in travelling."

"And I will," cried Frank; "I'll seek adventures and dangers in everypart of the globe--among the snows of the north, amidst the jungles ofIndia, in Afric's bush, and the wild plain-lands of far distantAustralia. I care not if I am killed; life without my Eenie is notworth having."

"Bravo! Frank," cried Chisholm, jumping up and shaking him by the hand."I'll go with you; and my friend, Fred Freeman, will go too. There'sluck in odd numbers. But don't talk about being killed; it is time thatwe want to kill, and all the wild beasts we can draw a bead upon."

Frank left the gloomy forest a happier man than he had entered it. Hewas laughing right merrily too.

"Bless that dear old fox, though," he was saying; "may he always bejolly and fat and frolicsome 'mid summer's sunshine or winter's snow.That fox was my fate."

CHAPTER TWO.

FRANK UNDERGOES THE PROCESS OF "HARDENING OFF"--CAMP-LIFE ON THE BANKSOF THE THAMES--A WEEK AMONG RABBITS--"'WARE HARE."

There was something about Fred Freeman which is difficult to describe,but which caused everybody to like him. He had the manners of ahigh-bred English gentleman, but that did not, of course, constitute thesomething that made him a favourite, because _bon ton_, manners arehappily not rare. However, there's no harm in my trying to describe himto you, because he is one of our three heroes. Fred wasn't much, ifany, above the middle height; he had a short dark beard and moustache--they were not black, however. He was very regular in features--handsome, in fact, handsome when he was in his quiet moods, which hevery frequently was, and even more so when merry, for then he was simplyall sunshine, and it made you laugh to look at him. He was veryunobtrusive. He was a capital shot, and a daring hunter and sportsman,but never boasted about his own doings. His constitution was as toughas india-rubber, and as hard as nails. If there be anything wanting inthis description, the reader must supply it himself. Anyhow, Fred was agenuine good fellow. He had hitherto travelled a good deal,sport-intent, chiefly on the Continent; but he jumped at the proposal togo round the world on "a big shoot," as he called it.

Freeman was a bachelor, and said he would always remain so; ChisholmO'Grahame was also a bachelor. Perhaps he was seen to the bestadvantage when his foot was on his native heath, and a covey of grouseahead of him. He was one of the so-called "lucky dogs" of this world.On the death of an uncle, he would come into a fine old Highland estate.Meanwhile he had nothing to do, and plenty of time to do it in. Afterhis visit to Frank, he went back to see Frank's father, who wasdelighted at the success of his mission.

"Ah," said he, "I'm so pleased! And so you must take the young dog off,and show him the world. But look here, he's in your charge, mind you;and if you take my advice, you'll show him some shooting in Englandbefore you go abroad. He's only a hot-house plant as yet; he wantshardening off."

Chisholm laughed. "I'll harden him off," he said.

And so the hardening-off process commenced at once. Frank was notsorry, after all, to leave the gloom of Epping Forest, and commence asportsman's life in earnest. The plan adopted by Chisholm and hisfriend, Fred, to "break young Frank in, and to harden him off," was, Ithink, a good one. They were to travel a good deal in England, be hereto-day and away to-morrow, and visit any of the fens or moors or shoreswhere there was the chance of a week or two of good shooting.

That was one part of the plan. The other was that they were, as Fredcalled it, "to forswear civilisation, and to live in tents;" in otherwords, to do a deal of camping out, instead of living in hotels orhouses of any kind.

"How do you think you will like that kind of thing?" asked Chisholm.

"Oh, I think it will be perfectly delightful," said Frank,enthusiastically.

"But Frank _is_ a bit of a shot, isn't he?" asked Fred.

"Always during vacation times," said Frank, speaking for himself. "Iused to potter around my father's property. I have done so ever since Iwas a boy."

"Ha! ha!" laughed Chisholm. "Why, you're only a boy yet."

"All stuff," said Frank stoutly. "I'll be twenty next birthday."

"Well, well," said Chisholm; "but tell Fred what you used to shoot."

"Oh, anything about the farms, you know, bar the song-birds; fatherthought it cruel to kill them. But there were rats, such lots of rats,and sometimes a hawk or a rabbit, or even a hare. Then there were thewild pigeons--wary beggars they are, too; I used to wait for them underthe fir-trees."

"What, and kill them sitting?" asked Fred.

"Well," said Frank, "it isn't sportsman-like, I know; but I could hardlyever get near them else. Then the young rooks were great fun in spring;and mind you, there is many a worse dish to set before a hungry man thanrook-pie."

"I believe you, lad," said Fred.

"Well, I've shot stoats and weasels by the score; and I once shot apolecat, and another day an otter, and another day an owl."

"Well, well, well," cried Fred. "What bags you must have made, to besure! Never mind, you've got the makings of a good sportsman in you.Chisholm and I will bring you out, never fear. Did you often goowl-shooting?"

"No," replied Frank; "I only remember one owl, and I don't know which ofthe two of us had the bigger fright--Ponto the pointer, or myself. Ihad killed nothing that day but one old rook, a few field-mice, and asnake or two, and we were coming home in the dusk, when some great birdflew heavily out of the ivy-covered old tree near the churchyard. `Downyou come, whatever you are,' says I; and bang! bang! went both barrels.He flew a goodly way, but finally fell; and off went Ponto, and off wentI in search of him. Ponto _was_ in a way, I can tell you; he wasn'tpointing half prettily. `Hoo! hoo! hoo!' the owl was screaming. `Comea bit nearer, and out come both your eyes.' `I'll stand here, anyhow,'Ponto seemed saying, `till master comes up.' Well, Chisholm, when Icame up and saw the creature, it looked

so like one of the winged imagesyou see on tombstones, that, troth, I thought I'd shot a cherub of somesort."

"Well done, Frank," cried Chisholm, laughing. "Now," he continued,pulling a letter from his pocket, "How will this suit? It is from afarmer friend of mine in Berkshire, a rough and right sort of a fellow.He farms about five hundred acres close to the Thames. He invites usdown for a rabbit shoot, shall we go?"

"Oh! by all means," cried Frank.

"I'm ready,"

Dick Merriwell Abroad; Or, The Ban of the Terrible Ten

Dick Merriwell Abroad; Or, The Ban of the Terrible Ten Wild Adventures round the Pole

Wild Adventures round the Pole Storm-Bound; or, A Vacation Among the Snow Drifts

Storm-Bound; or, A Vacation Among the Snow Drifts In the Yellow Sea

In the Yellow Sea Frank Merriwell's Triumph; Or, The Disappearance of Felicia

Frank Merriwell's Triumph; Or, The Disappearance of Felicia Treasure of Kings

Treasure of Kings Bert Wilson's Twin Cylinder Racer

Bert Wilson's Twin Cylinder Racer Frank Merriwell's Backers; Or, The Pride of His Friends

Frank Merriwell's Backers; Or, The Pride of His Friends Endurance Test; or, How Clear Grit Won the Day

Endurance Test; or, How Clear Grit Won the Day Great Hike; or, The Pride of the Khaki Troop

Great Hike; or, The Pride of the Khaki Troop The Swan and Her Crew

The Swan and Her Crew A cup of sweets, that can never cloy: or, delightful tales for good children

A cup of sweets, that can never cloy: or, delightful tales for good children Frank Merriwell's Bravery

Frank Merriwell's Bravery Frank Merriwell Down South

Frank Merriwell Down South Dick Merriwell's Trap; Or, The Chap Who Bungled

Dick Merriwell's Trap; Or, The Chap Who Bungled The Trail of the Seneca

The Trail of the Seneca Wild Life in the Land of the Giants: A Tale of Two Brothers

Wild Life in the Land of the Giants: A Tale of Two Brothers From Squire to Squatter: A Tale of the Old Land and the New

From Squire to Squatter: A Tale of the Old Land and the New The Cruise of the Snowbird: A Story of Arctic Adventure

The Cruise of the Snowbird: A Story of Arctic Adventure Owen Clancy's Happy Trail; Or, The Motor Wizard in California

Owen Clancy's Happy Trail; Or, The Motor Wizard in California Boy Scouts: Tenderfoot Squad; or, Camping at Raccoon Lodge

Boy Scouts: Tenderfoot Squad; or, Camping at Raccoon Lodge Sing a Song of Sixpence

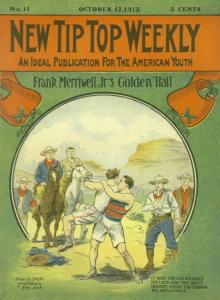

Sing a Song of Sixpence Frank Merriwell's New Comedian; Or, The Rise of a Star

Frank Merriwell's New Comedian; Or, The Rise of a Star The Sa'-Zada Tales

The Sa'-Zada Tales The Girl Scout's Triumph; or, Rosanna's Sacrifice

The Girl Scout's Triumph; or, Rosanna's Sacrifice Wild Adventures in Wild Places

Wild Adventures in Wild Places Fairies I Have Met

Fairies I Have Met Frank Merriwell's Son; Or, A Chip Off the Old Block

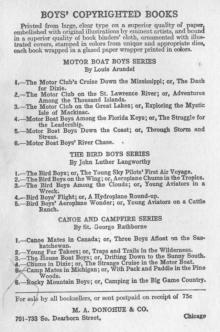

Frank Merriwell's Son; Or, A Chip Off the Old Block Motor Boat Boys' River Chase; or, Six Chums Afloat and Ashore

Motor Boat Boys' River Chase; or, Six Chums Afloat and Ashore Frank Merriwell's Athletes; Or, The Boys Who Won

Frank Merriwell's Athletes; Or, The Boys Who Won Bart Keene's Hunting Days; or, The Darewell Chums in a Winter Camp

Bart Keene's Hunting Days; or, The Darewell Chums in a Winter Camp Captain June

Captain June